- Home

- Frederic Martini

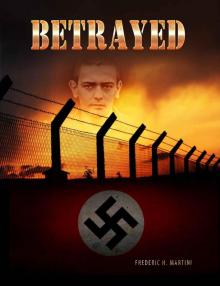

Betrayed: Secrecy, Lies, and Consequences Page 2

Betrayed: Secrecy, Lies, and Consequences Read online

Page 2

Sam was riding on Fred’s left. Next to Sam was Ervin Pickrel, the radio operator, from Parma, Idaho. Light-haired and over 6’ tall, Erv towered over the other sergeants and took considerable ribbing about it. He was a nice guy who generally kept to himself, seldom joining Fred, Sam, or other airmen on those rare occasions when they went out on the town.

Armando Marsilii, known to his friends as “Mandu,” was the only married member of the noncom crew. Mandu, the upper turret gunner and the lead flight engineer, was from Wilmington, Delaware. He was roughly 5’6” and 140 pounds, with thick black hair and dense, bushy eyebrows that often put his eyes in shadow. He had a small, new scar along his right temple, a souvenir from the ditching of the crew’s second B-17 in the English Channel a month earlier. Like Erv, Mandu seldom left the base on liberty, spending his free time snoozing, playing cards, or writing letters to his wife.

Felipe E. Musquiz was an enlistee whose family lived in Musquiz, Mexico. Felipe was a short bundle of energy. He had a ready smile, and a slender mustache that he probably thought made him look like Clark Gable. At 5’4”, Felipe was the smallest member of the crew, which might have explained how he achieved the singular honor of being the ball turret gunner. This was not only one of the more dangerous positions in the aircrew, but also the most claustrophobic. Although Felipe could climb into the turret on his own, once he was tucked inside, getting back out could be a struggle. Their first B-17, which they had flown from the US to the UK, had been named Crashwagon as a joke. Rather ironically, upon arriving in the UK, they found that their landing gear would not lower,1 and they were forced to do a belly landing in Langford Lodge, Northern Ireland. Because they had jettisoned the ball turret over Loch Neagh before attempting the landing, the other members of the crew took pleasure in reminding Felipe that they could have left him in the turret when they detached it. As was typical of crew banter, Felipe had a variety of rejoinders like, “Wish you had — I hear Irish girls are terrific.”

The tail gunner was Theodore Dubenic, from Chicago. Ted was 5’9” with a stocky build and relatively heavy features as compared to Fred or Sam with whom he often traveled off-base. He availed himself of every opportunity to see the sights when liberty passes were distributed, as he considered it to be stress relief. Only slightly less isolated than the ball turret gunner – with some effort, the tail gunner could crawl forward to reach the waist – from his station, Ted had amazing views of combat operations and potential threats astern as well as the relative positions of the planes in the formation. Information relayed from the tail gunner was often invaluable to the pilot and the aerial gunners whose fields of view were relatively limited.

As they bounced along in the 6x6, the men tried to make sense of their situation. The general consensus was that this was a SNAFU.2 They had been told that they were out of the mission rotation because they were going to Lead Crew School the next day, and Crashwagon III was in the maintenance hangar being prepared for training operations.

Fred and the other sergeants were pleased to have been selected for Lead Crew School. It was an acknowledgement that they were experienced and their bombardier was proficient. What they didn’t know was that it was also an acknowledgment of the high attrition rate in terms of planes and crews. The Army Air Corps was selecting and training experienced crews to lead missions and increase the survival odds for new air crews. It took time to train a bombardier to use the Norden bombsight, a complicated apparatus that factored in air speed, wind direction, and altitude to predict where released bombs would impact the ground. When short-handed, planes could be sent on missions without a bombardier, but under orders to maintain a tight formation and release their bomb load when they saw the lead crew drop theirs.

When the truck pulled up by the entry to the mess hall, Fred, Sam, and the other crewmen clambered down to join the stream of men heading for breakfast. The interior of the mess hall had a capacity of around 400 men. The arriving air crews hastily grabbed trays and went through the chow line collecting their usual breakfasts. The choices included reconstituted powdered eggs, bacon, corn flakes with powdered milk, toast, and black coffee.

Shortly after they were seated, the cluster of six sergeants was visited by their pilot, Lt. Loren E. Jackson. Jackson, 26 years old, was a striking young man who carried himself like a career officer. He had short brown hair, and his athletic frame carried no extra weight. He was from Douglas, Arizona, and had enlisted after graduating from the University of Arizona. At the time, college graduates volunteering for the Army Air Corps were usually assigned to either pilot, navigator, or bombardier training based in part on test results from a Classification Center and in part on the need to fill open positions. Loren had been able to talk his way into pilot training despite some lingering injuries sustained in a severe motorcycle accident several years earlier. It turned out he had a natural aptitude for piloting, and his competent, easy going nature made him a natural leader. Shortly before deploying to the ETO (European Theater of Operations), Loren had married Alice, four years his junior, in a quiet ceremony in St. Petersburg, Florida. His primary goal was completing the requisite thirty missions, going home, and reuniting with Alice. He was all business, and the carefree life of the single enlisted man was the farthest thing from his mind.

Confirming their suspicions, Jackson said that Major Masters had just apologized for waking them. Apparently there had been a screw-up in the paperwork, and the rotation wasn’t adjusted when Jackson’s crew was assigned to Lead Crew School and the plane pulled for maintenance. They now had two options: they could take the day off and go back to bed, and another crew would be hastily aroused to take their place, or they could go ahead and fly the mission. They had to decide immediately.

Jackson and the rest of the officers felt that since the entire crew was already up and dressed, they should fly the mission. Between flying as reserve or having missions scrubbed, their combat missions weren’t accumulating very quickly. They had fewer than one-third of the 30 missions needed to head stateside. Besides, Shaffer needed only one more mission to complete his tour and receive the unofficial but coveted Certificate of Membership in the Lucky Bastard Club, which the Bomber Group awarded to airmen upon completion of their combat tour of duty in the ETO. Getting to the point of completing one more mission was a distant dream for Fred, but he could imagine how disappointed Shaffer would be if they pulled the plug now.

Lt. Gerald Shaffer had been temporarily assigned to replace Lt. Lindquist, their navigator for their first set of combat missions. A small, earnest man, Shaffer had been hospitalized with food poisoning, missing two missions with his previous crew. As a result, when the other guys completed their 30th mission and were rotated home, he had stayed behind. This would be his 30th and final combat mission, and he was anxious to return to his parents in Cochranton, Pennsylvania. They all understood how he felt, and the sergeants quickly agreed with Jackson’s plan. He then headed back to the table he shared with the other officers in the flight crew, Lieutenants Ross Blake and Joseph Haught.

Blake, the co-pilot, from Great Neck, New York, was of lighter build than Jackson and about an inch shorter. He was a thoroughly competent and reliable character, and his sense of humor often had the other officers smiling. Haught, the bombardier, was from Grantsville, West Virginia. He had an uncanny knack with the Norden bombsight, and with only nine missions behind him, he was considered to be among the best bombardiers in the 385th. His bombing skill and Jackson’s steady leadership were the reasons they had been chosen for Lead Crew School.

At 0345, Fred heard the trucks pulling up outside to shuttle the assembled aircrews to the briefing room. The Jackson crew left the mess hall as a group, the ten men climbing onboard a waiting 6x6 truck in company with another complete aircrew. In convoy, the trucks ran west and then turned north into the area known as the Willow Woods, where they arrived five minutes later. The complex of operational buildings was immediately adjacent to the western end of the runways. The

briefing was held in a long building with concrete walls and a steeply pitched wooden roof supported by internal trusses. The hall could seat more than 50 aircrews on bench seats or small, folding wooden chairs. There were windows on either side, blacked out for the night, and a dozen bare light bulbs in reflector sockets dangled from the ceiling. The walls were covered by bulletin boards with notices, weather reports, news articles, and posters of friend/foe plane silhouettes. A pot bellied stove provided heat, although when full, the room tended to become uncomfortably warm. Smoking was permitted, and there were butt cans by the tables. By the time the briefing got underway, the air was heavy and thick with smoke.

At the front of the room was a raised platform set in front of a 12’x12’ wall map showing the ETO, which stretched from the North Sea to southern France and from west of Ireland to the eastern edge of the Black Sea. When Fred and the men filed in and took their seats, the map was covered by a black curtain. However, some important information was readily available to the flight crews. A tall blackboard along the wall to the left of the map showed the formation for the day’s mission. It was divided into three sections, one for each of three involved squadrons. The term “squadron” in combat was distinct from the four squadrons in the 385th BG. Organizationally, the 385th air crews were assigned to the 548th, 549th, 550th, and 551st Squadrons. In combat, however, a “squadron” was a group of planes flying together in formation.

Of the three squadrons in the mission, one was designated the Low Squadron, one the Lead Squadron, and one the High Squadron, each with 12-13 aircraft. The arrangement was designed to provide maximum protection for the group as a whole through the combined firepower of their 50-caliber guns but still allow each plane to drop its bomb load without striking another airplane in the formation.

Looking closely, Fred saw that planes from the 551st were assigned to the High Squadron, and the YY to the right told him that when the formation assembled in the air, two yellow flares would be fired by the lead plane in that squadron. On the blackboard within each squadron area, a simple T represented each plane, with the pilot’s name across the top and the last three digits of the plane’s serial number printed to the left of the stem of the T. He looked for Jackson’s name and found, to his discomfort, that their plane would fly “Tail End Charlie”— the least well-defended position in the formation.3

At 0400, the 38 crews slated for this mission were all accounted for, and when a voice rang out “Attention,” the airmen sprang to their feet. A tall man with an aggressive walk and a colonel’s wings strode from the entryway along a hastily-cleared path to the platform at the front, where he turned and faced the airmen. This was Colonel Elliott Vandevanter, the leader of Van’s Valiants. He was well respected as an officer and as a leader, and his tendency to fly the lead plane on difficult missions had endeared him to the entire bomber group. The colonel was a big man, tall, muscular, and very fit, with an engaging smile that revealed a slight spacing between his front teeth. His uniform was immaculate, the creases like knife edges, and the cut obviously tailored to fit. His only known failing, which the airmen found endearing, was his extreme nervousness when placed in front of an audience.

An aide swept the curtain away, and suddenly the routing and the destination became clear. All missions were hazardous, but those targeting Germany were particularly rough, and there was a general sigh of relief when the crews saw that they were heading to France instead. Col. Vandevanter explained that because the weather over Germany was terrible, the bombing effort would continue to focus on supporting the Allied ground forces in Normandy, and promoting the liberation of France. The situation remained perilous, as the Allies were at most 16 miles from the coast, and east of Carentan the advance had stalled just three miles from the beaches.

Major Jim Lewis, the Operations Officer, and Major McWilliams, the Intelligence Officer, provided the mission details as Jackson and the other officers took notes. Fred, jangled on coffee, and chain smoking Camel cigarettes, paid scant attention unless the information concerned the location of German fighters or heavy flak concentrations along their route. His ears perked up when he heard that they would have three P-47 fighters as escorts — it was great news, as a fighter escort significantly reduced the threat posed by German fighters. It was not going to be a terribly long mission, which was equally good news. Planes were to be ready to start taking off at 0700, with the last bomber in the air by 0720, and they would be back in time for a late lunch.

There would be 38 planes from the 385th BG on this mission, and their formation would be called Wing 4. Wings left British airspace in a long line called a “bomber stream” with each wing in an assigned position. The High Squadron of Wing 4 would be at 24,000’. The 385th would enter the bomber stream behind the wing from the 94th BG and be ahead of the wing from the 447th BG.4 Once over France, the bomber stream would break up and the wings would head for their specific targets. Wing 4 would bomb the marshalling yards at Montdidier, approaching from the southwest (downwind) to minimize drift. Montdidier was a major switching center for supplies headed west toward the front lines. The crews were shown aerial views of the target area. This was very useful for the navigators and pilots but of no concern for Fred. But he did look up when Major McWilliams showed a map showing their flight route relative to the estimated positions of German 88mm anti-aircraft batteries. When Fred looked at the map, it didn’t seem too bad, as their course would take them south and east of the flagged areas.

Major Lewis always concluded a briefing by synchronizing watches, and in preparation, the men exposed their watches and froze the hands with the second hand at 12. The set time would be at 0430 hours, and with a countdown of “five….four…. three…. two…. one…. hack,” nearly 400 watches started ticking in synchrony. Lewis concluded the briefing by reminding the officers to pick up the mission codes and charts on their way out.

From the meeting hall, it was a short walk to the buildings containing the locker rooms and the supply desk. Fred entered the locker room with the crowd and moved toward his assigned locker. He never really enjoyed the prep — when it was done, he felt like a toddler in a snowsuit — but he knew the importance of proper preparation. He would be manning his guns by an open port at altitudes where temperatures ranged from -40 to -50°F, and oxygen levels were too low for survival.

Fred stripped down and pulled on his long johns, put his uniform back on, and covered it with a khaki flight suit. He then stepped into a one-piece “bunny suit” that looked like pajamas designed for a giant toddler. Fred loved his bunny suit, even if it wasn’t stylish, for when it plugged into the aircraft’s power supply, it was as warm as an electric blanket. He sat down on the bench seat by the locker to pull on his boot liners before getting into his heavy, fleece-lined leather pants and bomber jacket. He then rigged his emergency oxygen bottle and his survival kit, which held a compass, a silk map, money, and other useful items, including a small medical kit. He rechecked his gear bag to make sure that his flight cap, goggles, oxygen mask, and gloves were there before sitting down to pull on his boots. Fred closed the locker door, slung his gear bag over his shoulder, and worked his way through the crowd toward the exit.

Leaving the locker room, he turned right and walked to the next building to pick up his Mae West inflatable life jacket, his parachute harness, and his parachute — three items that needed inspection and routine maintenance after each mission. Once he had collected them, he returned outside before pulling the Mae West over his head and securing it. He then donned and adjusted his parachute harness. Like most of the airmen, Fred found the groin straps restricted his movement, so he tended to leave them a little loose.

Ready to head for the plane, Fred carried his parachute and gear bag toward the 6x6 trucks that were shuttling air crews to their planes. Partial aircrews gathered on either side of the road, climbing onto a truck only when the crew was complete. It was now around 0515. The sun had yet to rise, but there was certainly sufficient light for Fred

to recognize the other members of his aircrew. Although the officers wore flight gear similar to that of the enlisted men, their uniform caps set them apart, and most were carrying leather briefcases containing various mission papers, code books, area maps, personal logs, checklists, and other items. Only when all of the men were present and ready to go could Lt. Jackson give the driver the ID number of the plane they would be boarding, at which point the men boosted their gear up and boarded the truck. Once two air crews were aboard, the truck headed to the airfield.

The truck offloaded the Jackson crew alongside the plane they would use for this mission. Like most of the planes of the 385th BG at this time, it was painted a dull olive drab, although newer planes arriving from the US were a bright, unpainted aluminum.5 A previous aircrew had named the plane “Junior,” and the initial J was used for identification and radio instructions within the squadron. Junior was adorned with nose art showing the name and a skinny yokel in shorts preparing to throw a couple of lit sticks of dynamite.

Like the other planes they had flown, Junior was a B-17G, the newest iteration of the design, and the most heavily armored and armed. It was 75’ in length, with a wingspan of 104’, and its spindle-shaped fuselage was roughly 9’6” in diameter at the waist. There was little room to spare given that this relatively small volume had to carry the flight control and navigational gear, the generators and cabling, communication lines, hydraulic lines, fire extinguishers, oxygen lines and bottles, tools, radio equipment, and thirteen 50-caliber machine guns (2 chin, 2 cheek, 2 top turret, 1 radio room, 2 ball turret, 2 waist, and 2 tail), plus ammunition, survival gear, parachutes, 10 men, and 6,000-8,000 pounds of bombs.

Betrayed: Secrecy, Lies, and Consequences

Betrayed: Secrecy, Lies, and Consequences