- Home

- Frederic Martini

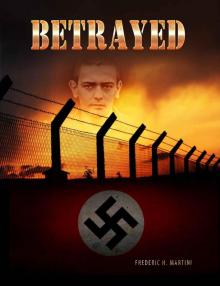

Betrayed: Secrecy, Lies, and Consequences

Betrayed: Secrecy, Lies, and Consequences Read online

Betrayed

About the Author

FREDERIC H. MARTINI, PHD (CORNELL 1974) is the lead author of ten undergraduate textbooks, two Atlases, and five clinical manuals in the fields of anatomy and physiology or anatomy. He has also written a book for amateur naturalists, and his professional publications include journal articles, contributed chapters, technical reports, and magazine articles. Betrayed started as a story about his father’s experiences in WWII. It evolved over seven years, as he unearthed declassified wartime and post-war documents held in the national archives of the US, UK, France, and Germany. Those seeking additional information about the author or about Betrayed should visit www.fredericmartini.com.

Betrayed

SECRECY, LIES, AND CONSEQUENCES

Frederic H. Martini

© 2017 Frederic H. Martini, Inc.

All rights reserved.

Cover design by Brandi Doane McCann, http://www.ebook-coverdesigns.com

ISBN-13: 9780999155806

ISBN-10: 0999155806

Table of Contents

Dedication

Introduction

Prologue

Part 1: Wartime

Chapter 1 12 June 1944, Great Ashfield, England

Chapter 2 Reverie

Chapter 3 Combat

Chapter 4 12 June 1944, Peenemünde, Germany

Chapter 5 Evasion and Capture

12-16 June 1944: Chauvincourt, in Occupied France

June-July 1944

17 June to 5 August 1944: Hacqueville and the Raulins

5-15 August 1944: Paris

Chapter 6 Striving for the Fatherland

Chapter 7 Transport

15-20 August 1944

Chapter 8 Arrival in Buchenwald

Chapter 9 Adjustment

The First Week in Buchenwald

The Second Day

The Third Day

The Fourth Day

The Fifth Day

The Sixth Day

The Seventh Day

Chapter 10 Endurance

The Second Week

The Third Week

The Fourth Week

The Fifth Week

The Sixth Week

The Seventh Week

The Eighth Week

The Ninth Week

Chapter 11 Stalag Luft III

Transport and Arrival

Orientation

Settling In

Christmas on the Home Front

Chapter 12 Vengeance

August-December 1944

Chapter 13 Into the Storm

Chapter 14 Stalag VIIA

Chapter 15 A Strategic Retreat

Chapter 16 Revelations

Nordhausen

Weilheim to Oberjoch

Planning for the Future

Part 2: Peace, Politics, and Injustice

Chapter 17 The Long Way Home

Chapter 18 The Spoils of Victory

The Mittelwerk

Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany

Washington, DC

Operation Overcast and Project Backfire

Chapter 19 Re-entry, 1945-1948

Chapter 20 Project Paperclip, 1946-1948

Chapter 21 Divergence

1949-1951

1952-1955

Chapter 22 Convergence

1956-1960

1961-1970

Chapter 23 Unraveling

1971-1977

1978-1995

Epilogue

Appendices

Appendix 1: Glossary, Abbreviations, and Personnel

Appendix 2: The French Resistance versus the Nazi Secret Police Network

Appendix 3: Buchenwald Airmen

Appendix 4: Lamason, the SOE, and Plans to Escape from Buchenwald

Appendix 5: List of Awards Received by Wernher von Braun

Appendix 6: Congressional Failures

Appendix 7: Acknowledgments and Sources

Dedication

To my father - better late than never

Frederic C. Martini

(1918-1995)

Photographs and chapter notes for each chapter can be found in the related section of the author’s website:

https://www.fredericmartini.com

Introduction

ON 22 JULY 1944, HITLER issued a decree that all Allied airmen captured in France should be turned over to the SS for execution. On 11 April 1945, the Dora Concentration Camp at Nordhausen was liberated, and American forces entered the associated underground V-2 rocket factory known as the Mittelwerk. These two seemingly unconnected events would irrevocably disrupt the lives of 168 Allied airmen who had the misfortune to fall into the hands of the Gestapo in 1944.

This is a story of betrayal, lies, secrecy, and consequences. It begins in June 1944, six days after the Normandy invasion, and extends to the current day. Although many people are involved, there are really three major players: my father, Frederic C. Martini, who was one of the affected airmen; the German rocket engineer Wernher von Braun, who was involved with the conception and operation of the Mittelwerk; and the intelligence services of the US government.

The issues raised by this tale are as relevant today as they were in 1945. At that time, Army Intelligence (G-2), Naval Intelligence, and the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) had been operating with few constraints for several years. Their leadership ranks had come to believe that because they knew secrets withheld from other agencies of government, they were in the best position to make key decisions on national security. Some of those decisions were misguided, others unethical, and a few illegal. All were hidden by a comprehensive and wide-ranging security program that used a combination of dissembling, disinformation, lies, and “alternative facts” to further their goals.

Secret programs brought hundreds of former Nazis, including SS officers and suspected war criminals, to the US to prepare for an anticipated war against the Soviet Union. The groups imported included Wernher von Braun and other members of the V-2 rocket program. Their wartime histories were secret, the existence of the Mittelwerk was secret, and the fact that the skilled slave laborers at Dora came from Buchenwald Concentration Camp where 168 Allied airmen had been held, was secret. The security lid covering von Braun, Dora, Buchenwald, and the Buchenwald airmen did not lift for decades, while the public at large remained completely oblivious.

For almost 40 years, my father and the other American airmen held at Buchenwald were told by the government they had suffered to defend that they were either delusional or liars. The Army, the Veterans Administration, and the US Congress denied their experiences and refused to provide substantive support for the mental and physical damage they had endured.

When I started working on this story, I knew only the barest details. I was always aware that my father was haunted by the war. His mood swings, especially his sudden rages, were simply part of our daily lives. He seldom spoke about the war, but as a child, I overheard his conversations with other veterans, and once I reached adulthood, he would sometimes tell a story to illustrate a point about wars and history. By the time his health started failing and his battles with the Veteran’s Administration heated up, I was away at college, then graduate school, and then building a career. I occasionally heard about my parents’ frustrations, but didn’t learn just how extensive the problems were. My father felt that it should be his battle, not mine.

After my father died, my mother moved to Hawaii, where I had settled with my wife and son. In 2010, as she was getting prepared to shift to an assisted living facility nearby, I started going through her “stuff” to see what she might want to take with her. I was stunned to find several sealed bo

xes labeled “Fred Military” and “Fred VA,” each packed with documents. I also found vacuum-packed bags of correspondence from WWII. That cache of evidence was the catalyst for this seven-year project.

It has been a wild ride, taking me to Normandy and Paris, to the US National Archives (NARA/College Park) in Maryland, to the National Air and Space Museum (NASM) in Virginia, to the US Holocaust Memorial Museum in DC, to various WW II museums, and into the navigator’s chair on a B-17 flight. What started as a story about the trials and tribulations of one Buchenwald airman dealing with the Veterans Administration soon led me into the labyrinth of Project Paperclip, the postwar importation of Nazi engineers, and the oppressive and sometimes heavy-handed application of government secrecy. It became a story about my father as a “friendly fire” casualty of decisions made in the interest of national security by intelligence agencies operating in the absence of public, congressional, or executive oversight.

This is a true story, not a novel. The narrative has been based on declassified records, survivors’ accounts (either published, recorded, or filmed), and war crimes trials and depositions. However, there are multiple uncertainties to be expected when attempting to reconstruct events that occurred more than 70 years ago, based on multiple accounts that may or may not overlap. These men were under extreme stress, and each airman’s perspective was so limited that none were aware of everything that happened. Over time, memories fade or change, and in most cases, the airmen did not talk about these events until decades later. Where conflicting accounts exist, the narrative follows the consensus view. And although the events are documented, with few exceptions, the thoughts of those involved had to be inferred from what their actions and patterns of behavior reveal about their personalities.

Prologue

I A.M. THE HOUSE IS cold and silent. His wife and son are asleep, but he hates going to sleep, for his dreams are too terrible. He’s been at home for the last week, after losing his job because he can’t stand on his aching feet all day. He dresses quietly, donning his leather jacket against the chill. He goes to the bedside bureau and quietly begins tossing clothing into a pile on the floor. His wife, awakened, asks him what’s wrong. He doesn’t have an answer for her — his actions have a momentum of their own.

Soon the pile contains all of his uniform gear, from his socks to his dress uniform with various medals attached. He gathers the pile in his arms and goes out of the room and down the stairs and passes through the dark kitchen through the back door and onto the porch. Each painful step is a reminder of the horrors of Germany and his humiliation at home.

It is a relatively quiet neighborhood, but a passing car backfires. With no grasp of the intervening moments, he finds himself crouching, pressed against the wall of the house, his clothes scattered before him and down the steps to the small, enclosed back yard. He is gasping and shaking. As he regains a semblance of control, he gathers up his things and moves from the stairs to the far back corner of the yard, where a burn barrel stands empty.

The November sky is clear and moonless, and the stars above glitter like shards of broken glass. It is a chilly night, but not bitterly cold, yet he is shivering as he stuffs his gear into the barrel. A moment’s search locates the Mason jar that holds the gasoline for fire starting, and he pours a generous amount over the piled clothing. When he pulls a matchbook from his pants pocket, lights a match, and drops it into the barrel, the saturated contents ignite with a whoosh.

He watches the fire for a time as if hypnotized, and then with a start realizes that his task is still incomplete. He shrugs off his leather flight jacket and tosses it onto the flames. By chance, the jacket lands with the chest up, with his name in view, and the sight of that familiar jacket, and the flames, and the pitiless sky trigger an avalanche of memories that he fights to suppress. As he stands in the radiated warmth of his burning history, with his emotions a mixture of frustration, rage, and grief, his wife watches from the porch in silence. But his actions, although cathartic, change nothing. His troubles are far from over.

Part 1: Wartime

There is only one thing certain about war, that it is full of disappointments and also full of mistakes.

WINSTON CHURCHILL, 27 APRIL 1941

CHAPTER 1

12 June 1944, Great Ashfield, England

AT 0230, STAFF SERGEANT FRED Martini was awakened by a sharp tap on the forehead and a bright flashlight in the eyes. The flashlight was held by Major Vincent Masters, who told Fred to be on the truck in 30 minutes, before moving on to the next airman on his wake-up list. Fred rummaged in the darkness for his kit bag in the knapsack stuffed under his berth, while in the bunk above him, he could hear his friend Sam getting his gear together. Still a bit muzzy headed, he got to his feet and headed to the softly lit washroom. After hastily using the facilities, washing his face, and shaving, he returned to his bunk, again in darkness, and quietly donned his uniform, taking it off the hangers hooked on the rails at the foot of his bunk.

The small Quonset hut barracks held the noncommissioned officers from two flight crews of the 385th Bomb Group (BG), but only Fred’s had been awakened for duty. As Fred and the five other sergeants left the barracks, they crossed the dirt road toward a line of GMC 6x6 trucks, their headlights damped and deflected downward by horizontal strips of electrical tape. They picked one and climbed up into the uncovered cargo area, moving to the front as bomber crews from other barracks climbed in behind them. From the hour and the crowd, Fred knew that this would be a combat mission rather than a training exercise, and he assumed that comparable pickups were being made at the barracks areas of the 548th, 549th, and 550th Squadrons.

Although there were narrow, wooden bench seats available, most of the men chose to stand, knowing that the ride over the unpaved, rain-rutted roads would be brief but bouncy. Once everyone was aboard, someone banged on the roof of the cab, and the truck revved up and headed to the mess hall just over a half-mile away.

Fred braced himself and scanned the skies to see what kind of a day it would be. The predawn hours were cool and clear. The temperature hovered around 50°F, with a dampness in the air that was a lingering reminder of the heavy rains that had cancelled missions two days earlier. A quarter moon struggled to cast its light from just above the eastern horizon. Although partially obscured by a layer of low cloud, the moon still provided enough light to silhouette the tips of three trees that stood alongside Runway 24. The buildings, planes, and the airfield itself were all in darkness, blacked out or unlit to make it harder for a German pilot to locate.

The night air carried a mixture of smells dominated by oily smoke, diesel exhaust, and aviation fuel, and Fred knew that some of those smells lingered from the bombing of the field three weeks earlier that destroyed a maintenance hangar and blew the B-17 bomber “Powerful Katrina” to smithereens. He had been hiding under a Jeep feeling extremely vulnerable while that air raid was underway — that was not a favorite memory. But then the industrially tainted air mass parted, and there was a gust from the surrounding countryside that triggered memories of spring growth and flowers. Fred found it a bit unsettling. It was a transition from wartime to peacetime in the space of a moment.

The truck soon reached the end of the access road and made a hard right as it turned toward the communal mess hall. Fred looked around the truck at his crew, some still half asleep. They had been through so much together already — months of intense training, nine combat missions, and two crash landings — that they had been welded into a cohesive unit.

Like most aircrews in the Army Air Corps, Fred’s comrades, all sergeants, came from all over the US. None of them had gone to college, and some had not completed high school. Fred Martini, at 26, was one of the senior hands. Born and raised in Brooklyn, he was cocky and street wise. Lean and handsome at 5’10” and 160 pounds, he wore his uniform with panache and adopted a jaunty attitude. After the crew’s exploits in New York City, Fred was widely hailed as a “ladies man.” But although the other

sergeants at times still called him “Valentino,” his amorous interests were on hold for the duration. It was hardly surprising, given that Great Ashfield was remote, the base was dry, and with missions every day or every other day, there was no time in any case.

Fred served as left waist gunner (LWG) and assistant flight engineer for his crew. He manned a pair of 50-caliber machine guns mounted just aft of the left wing, defending that side of their B-17 bomber. The right waist gunner, Sam Pennell, protected the right side with a second pair of 50-caliber guns. The plane was too narrow for the two men to work back to back, so the guns were staggered, with the left waist gun forward of the right waist gun and the two gunners facing one another. Sam was 5’9” and 145 pounds, hailing from Columbus, Georgia. His wavy, brown hair was closely cropped, framing a narrow face with a sharp chin. Sam had a friendly disposition and a competent air, and everyone liked him immensely. Although more reserved than Fred, after training, berthing, and flying together for nearly a year, the two had become close friends. At Drew Field, in Florida, they had filled their off days at the beach or in the bars in Tampa, whereas at Great Ashfield, there was little to do other than play cards, shoot pool, or swap stories.

Betrayed: Secrecy, Lies, and Consequences

Betrayed: Secrecy, Lies, and Consequences